The evolution of ceramics processing in human history

The history of ceramics

Ceramics is an artisanal technique knowed since prehistory. It’s supposed that its creation happened in two place independently, between Saharan people and in Japan, spreading from there in all the World.

The first artefact belong to the Neolithic: crude pottery hand-shaped and baked directly on a fire. Later, the lathe and other technical innovation were introducted, that allow the production of more fine and strong item.

Painted ceramics were exported from Anatolia and the Fertile Crescent to Europe around the III millennium BC, reaching Greece after the fall of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilization. From VI to IV century BC, in Athene and other regions like Beozia, Etruria and the Magna Grecia, mani centers of production arises.

In roman age the aretinian ceramics spreads – known for its relief decorations – and the “sealed dirt” type, that remained in use until the fall of the Roman Empire. Of the same age, around the 1000 AC, the majolica was inventend in an atempt to copy the oriental products.

In the late Middle Ages ceramics were made with the lathe, baked and waterproofed with glaze, but in the XIII century more advanced and colorful decoration was introduced. In this period the major production centers of central Italy were developing: Orvieto, Siena and Faenza. The evolution of decoration and style will continue in the next two centuries, but it wasn’t until the seventeenth century that an actual jump ahead in the quality will be made. Thanks to the work of the alchemist Böttger from Meissen, the kaolin was introduced in the working process, making western ceramics as hard as cinese porcelain.

The industrialization of the late eighteenth century gave more boost to the processing and the developing of new technique, allowing a rise in the productivity and the lowering of the costs. A century later new solid improvement, like the tunnel oven and the atomizer, were introduced; with this new technology the industry could reach the even bigger size of production that the expanding market demand.

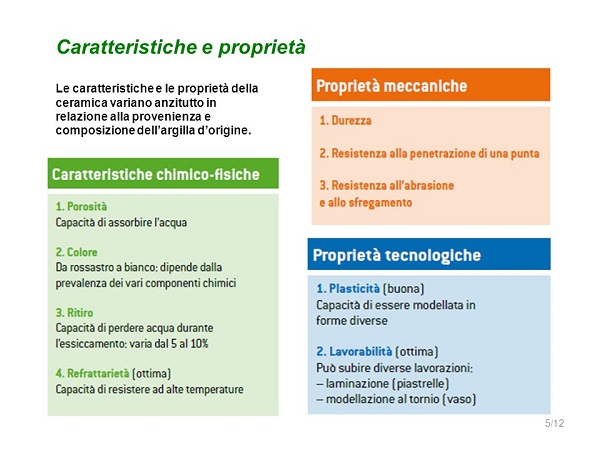

Characteristics

The word “ceramic” comes form the ancient greek “kéramos”, that means “potter soil”. It’s a composed material, inorganic, non-metallic, very ductile in its natural form and stiff after the sintering process. Thanks to its plasticity it’s possible to use it to create a vast variety of items like pottery, ornaments, building material, medical protesis, insulated coatings and so on.

The color of ceramics can change depending on the different chromophore oxides in the clay (iron oxides for yellow, orange, red and brown, titanium oxides for white and pale yellow), and it can also be coated and decorated.

Ceramics is usually made from different components: clay, feldspars (of sodium or potassium), silica sand, iron oxides, alumina and quartz. This complicated composition are characterized by the presence of flat molecular structures known as phyllosilicates. The shape of those structures, in the presence of water, gives to the clay a certain degree of plasticity and allows its manipulation.

Type of Ceramics

There are four kinds of ceramics, divided in two differen type: the compact and the porous ceramics. The firsts have a very low level of porosity, are waterproof and so hard that even a steel point can’t scratch them. Belongs to this category porcelain and stoneware. The second type ceramics have a more tender and absorbent mixture, and they are divided in terracotta and clay.

Porcelain

It’s considered the most fine level of oriental ceramics production. The main component is a particular white clay called aluminium silicate hydrous kaolin. The kaoilin gives plasticity and white color to the porcelain. It also contains quartz that works as an inert component and has a degreasing function, other than helping with the vitrification. In addition there is also feldspar that, with a lower fusion point than the kaolin, makes the whole fusion point of the mixture dropping down to 1,280 degrees celsius.

Stoneware

Used mostly for domestic and building tiles production, is obtained from a mixure of natural clays that makes a particular kind of ceramics known as “greificate”. The production needs a temperature which oscillates between 1,200 and 1,350 degrees celsius. The coloration can change due to the different iron compound in the mix: for a white stoneware – for exemple – it’s used a mixture of white clay and quartz-feldspat rocks similar to the ones used for making porcelain.

Terracotta

This kind of ceramics shows a coloration that mar vary from yellow to dark brick red, thanks to the presence of salts and iron oxydes. The presence of those compounds also improves the mechanical strong and helps in the vitrification process during the sintering stage, that usually reach 980-990 degrees celsius. Thanks to its stability, its resistance to ageing and the lightweight due to its porosity, terracotta is the most widespread building material. It’s used both without and with coating, for bricks, vases and structual or decorative objects in the first case, and for pottery in the second.

Argil

It’s a very malleable ceramic for the high levelo of water its structure that improves the plasticity, and so it’s really easy to handle even without tools. Its sintering temperature can vary due to the quantity of alumina inside. When dried is really fragile and rigid, but it acquires hardness after the sintering process.

Artisanal ceramics productive cycle

In the artisanal production specific type of clays are selected based on the particular manufacture intended. The most common are kaolin, sandy clay and fireclay, specifically design to withstand high temperature.

Regardless of the variety chosen, the clay is not ready to be used. It needs to be cleaned from impurity through a process known as “seasoning”. After that it is dissolved in water for washing away the salts. Finally it undergoes another cleaning to remove the last impurity and the coarse-grained particles.

A subsequent processing revomes air bubbles and makes the mixture more compact, preventing the formation of cracks at the end of the manufacture. At last, chamotte is added at the mixture – a powder obtained by grinding previously baked ceramics that makes the product more resistant to heat shocks.

Forming

There are many ways to forming the mixture. It can be by hand, with the “colombino” technique – also known as “lucignolo”, where the material is divided in modular strips, stretched and lying one on another – or dividing the clay in sheets from which cut the shapes of the various components. The most common tool-forming methods are the lathe or the die. The lathe is mostly used for pottery making, and it uses a rotating plate that allows the craftman to modeling the piece on a symmetry axe. In the second a plaster mold is filled with liquid clay. The plaster helps the drying absorbing the water from the mixture, and after a set time the piece is extracted from the mold and finished by hand.

Drying

Whatever is the technique chosen, is necessary for the clay to dry completely at open air. It’s a very delicate passage, because from the homogeneity of this process depends the longevity of the object. After a certain amount of time the clay reach the state in which it’s good for incision and decorations; this state is usually called of leather hardness. At the end of this stage, is possible to proceed to the sintering.

Sintering

Probably the most important part of the productive process, sintering happens in special ovens that can reach over 1,000 degrees celvin, according to the specific material. This stage can last several hours, so that the temperature can follow a specific curve of gradual increase and decrease. At the end of the process the product will have lost some volume.

Enamelling and Decoration

There are various techniques for decorating and colour ceramics, based on the type of object and the kind of sintering needed. Basically is possible to distinguish two main techniques: the “ingobbio”, that allows to decorate the manufact before the sintering stage, and the after-sintering decoration that requires a second passage in the oven to obtain the vitrification. The ingobbio are colours specifically for ceramics, composed from baked and fine-grinded clays. This glazes are design to be applied to the raw dryed object; this allows to skip a passage and bake the piece just one time. The ingobbio aren’t very popular because they are expensive and creates a really pale coloration. The vitrification happens during the only sintering stage, so it is necessary that the temperatures of the clays in the ingobbio and the ones in the object are the same.

Cristalline and enamel, on the other hand, are applied on the baked piece, and for that they requires another sintering passage for the vitrification. The first, known also as vetrine, are waterproof and shine, but are also transparent – even if they can be colored – and had the propriety to show the clay beneath. At this kind of enamel are added fondants like germanium, borates or alcohols to lower the melting point. Enamel are the same glass-type overlay of the cristalline, but they are opaque. They can be shiny or can be frosted by adding zinc or calcium oxydes which crystallizes during the cooling fase.

Enameling has the purpose to prevent wear and facilitate painting and maintenance. After the process is complete, the object can be decorate – usually by hand with specific ceramics colors.

Industrial ceramics productive cycle

Industrial procedures for mass-production of tiles and other kind of ceramics are divided in single and double sinter. The firs one is generally used after a wet process and it goes through a single baking after drying and enameling. The double sinter procedures rekon on a dry process in which there are two baking: the forst for sintering the support, the second for the vitrification of the enamel.

Raw material preparation, drying and sintering

The aim of preparation is to have a homogeneous mixture. The fine granulometry allows a right drying speed and a good reactivity during the sintering, while the grains shape and the moisture of the mixture determine the uniformity fo the pressed. The water content of the mixture should be appropriate to the particular forming system chosen:

Dry pressing – commonly used for tiles, it needs a water content of 5-6%

Extrusion – is the metod for making bricks, it needs a water content of approximately 20%

Slipcasting – it’s used for bathroom furniture, and it needs a water content of 40%

After the forming it’s time for drying and sintering. The ceramics materials came from powders that melt down with high temperature and mixt together in a solid hard, material.

Enameling and second sintering

The enameling can happen between the two baking or before the only one in case of a single sinter. This passage serves for both the look of the piece and its practical use: regadless of the translucent or opaque enamel used, the final result is a waterproof and insulating coating. In some ceramics lead oxides are added to the enamel to lower their baking point and save on the costs. Porcelain, on the other hand, needs vetrina without lead, and the baking temperature can reach 1,500 degrees celsius.

The Art of Ceramics in the italian old workshop

From Renaissance to the Nineteenth Century

In the Renaissance the italian ceramics became the most important in the european landscape. The main regions are Lazio, Umbria, Abruzzo, Marche, Tuscany and Veneto. In Lazio ceramics are inspired by late Romanesque style, with simple glassy crockery with duotone decoration in green and brown. Among the most characteristic products there is the “panata” mug, originally intended for the bread soup.

Abruzzo saw the rising of the Castelli’s workshops, particulary the Pompei furnace. The Castelli’s production in the early sixteenth century it’s almost all from high commissions, to the climax to this fine quality manufacturing: the monumental set of the Orsini/Colonna pharmacy, with its rich and diversified bright-colored crockery. The artistic production in Abruzzo is characterized by articulated forms – whose origins are in the renovation between Mannerism and Baroque – and lapis lazuli blue enamel with golden pictorial detail.

In Umbria, after a remarkable medieval phase, the majolica art stands in the late fifteenth century in all the italian marketplace with original polychrome crockery in a Late Gothic style for pharmacy sets. In the begining of the sixteenth century big royal plates and table sets appears, both in polychromy and blue alone, enriched with metallic colors of reds and golden yellows. This technique, an original invention of the Middle East workshops, arrived in Europe and Italy through the spansih craftmen and the commercal traffics with Mallorca – from which the word “majolica” comes. The same technique was used in Umbria for some decades; in Deruta and, with some particularly excellent results, in the workshop of Mastro Giorgio Andreoli in Gubbio.

Starting in the second decade of the sixteenth century, in Marche the ceramics production was specialized in figurative and historiated decoration, usually transferred from the mediation of the reproduction of Raffaello’s works.

The art of majolica in Tuscany emerged in Cafaggiolo and Siena. In here, the production presents some typical jars decorated with “grotesque”, geometry and palmette that highlights how the vase manufacturing was in tuning with the floors of the same period. In Cafaggiolo in the mid sixteenth century, on the other hand, there is a excellent production of porcelain-like ceramics in blue on white with the mediation of Middle Est workshops. Those imitations are found also in Faenza, Venice and Liguria, but only in Florence the late sixteenth there are trace of real europian porcelain, thanks to the supporto from the Medici family. It is a compact and polished porcelain, rigorously in blue on white, known as “porcellana medicea” due to the patronage of the Medici to the research, and it’s documented by about fifty piece in all the world.

The Renaissance production in Veneto rotates mainly around the Venetian workshops. The products of this marketplace stands out on a technical level, mostly for the quality of the majolicas and the colors of the rich glassiness, that seems to have benefited form the same matter used in the celebrated local glassworks school. in the first half of the sixteenth century the main themes was the “trophies” and the “grotesques”, painted in grisaille on a dark blue and cyano field, in which the Maestro Ludovico was an excellence. In the later decades the Venetian marketplace is dominated by the figure of the Maestro Domenico, whose workshop gave birth to pharmacy sets of exuberant leaves and portraits decoration, a manifest of Venetian painting.

Bioceramics

The ceramics has always been used to realize object with the goal of performing specific functions: just think about the vastity and heterogeneity of the pottery production through the various human civilizations. In those cases the research for the form wasn’t often limited to the mere function, but also had an aesthetic intent that transcended the simple technical goal.

In the field of advanced ceramics the pratical performing doesn’t leave much room for many formal solution. Most of the time the object can have only a particular shape in order to work properly. This is particulary true in the field of biomedical ceramics, in fact in this field more than any other the more correct term should be “component”, as in body parts replicated in an efford of total mimesis. Their apparent simplicity it’s the result of a complex research that connect various fields of study and fine technology.

There is nothing new in the aimed purpose: there is a lot of evidences of prosthetics made from different materials through the history of ancient civilization. But wiht biomedical ceramics the expression of our primordial self-preservation instinct reached, in the last decades, resoults of greath effectiveness. The research today is moving towards the reduction of the operations invasivity, designing more longeval prostetic to limit the needing of revisions on one hand, and stimulating a human body reaction to regenerate itself on the other.

Another important contribution is offered from the advanced ceramics devices for diagnostics, therapeutic activities and surgery. Observing this biomedical ceramics recalls ourself to the awareness of the perfection of our body and, at the same time, its vulnerability. The quality of our lives can be strongly conditioned from this tiny machines that are responsable not only of our organism functions but also of sophisticated medical equipment.

Source: MicFaenza

Protagonists of the twentieth century

The italian ceramics in the twentieth century can vaunt a record in the european marketplace for the quantity of its production and its quality level.

During the last century the art of ceramics has emancipate form a minor role and gained a equal place with other forms of artistic expression. Potters, architects and artists have contrbuited to this decisive step whose works are witnesses of the lability of borders between painting and sculpture. Beside that it should be noted that ceramics contributed in a lots of ways realtive to new trends like Art Nouveau, Futurism or Informal, to the point that it deserves a pace in the history of modern art.

Lucrezia Piscopo Art, winning project of the Lazio MarteLive 2021 regional final

Interview with Federica Rezzi G, winner of the Lazio MarteLive 2021 final, crafts section

From tradition to today, a special gift for a special professional

The beautiful works of Klimt on the ceramic eggs of La Terra incantata

Valentina Musiu and VALEgnameria, art and craftsmanship in a dynamic and colorful mix

Lunamante Goldsmith workshop, the Covid don't stop creativity