The Ancient Art of Wrought Iron

The ancient art of wrought iron mingles its origins with the very origins of man. Despite the fact that iron is the most abundant element in nature, its spread has historically been very slow and difficult.

Origins

The evolution of man is marked by learning the necessary secrets for the use of this metal. The Iron Age (1000 BC), which followed that of stone, was a huge step forward for mankind.

Although solid metal tools and weapons have been known for a couple of millennia, the history of wrought iron was born many centuries later, when the men of that time realized that the mass of molten iron had to be heated again to be subsequently forged and modeled according to different needs. The figure of the blacksmith – also surrounded by a magical aura – became soon very important in society and in civil organization, as demonstrated by many episodes of Greek mythology.

Characteristics

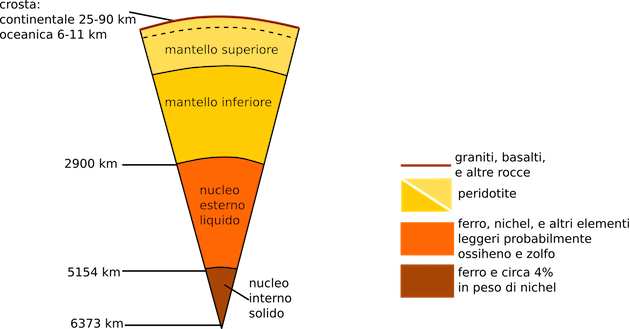

Iron is the most abundant metal within the Earth (constitutes 34.6% of the mass of our planet) and is the fourth most abundant element in the Universe. The concentration of iron in the various layers of the Earth varies with depth: It is in its maximum in the core, which is probably formed from an alloy of iron and nickel and decreases to 4.75% in the crust. However, the large amount of iron present in the center of the Earth cannot be the cause of its magnetic field, since such element is located with all probability at an elevated temperature, where there is no magnetic ordering in their crystal lattice (this temperature is called the Curie temperature). Its symbol Fe is an abbreviation of the word ferrum, the Latin name of the metal.

Iron is a metal extracted from minerals: no pure iron is found in nature (native). To extract iron from its ores, inside of which it’s in the oxidized state, it is necessary to remove impurities by chemical reduction. The iron is usually used to produce steel, which is an alloy based on iron, carbon and other elements.

The iron nucleus has the highest binding energy per nucleon, so it is the heaviest element that can be produced by nuclear fusion of the lighter atomic nuclei and lighter than can be obtained from fission: when a star exhausts all the other light nuclei and comes to be composed largely of iron, the reaction of nuclear fusion in its core stops, causing the collapse of the star on itself and gives rise to a supernova. According to some cosmological models, it is theorized that at an open universe, there will be a phase where as a result of slow fusion reactions and nuclear fission, the whole matter will be converted into iron..

The use of wrought Iron at the time of the Romans

The same happened during the era of the Roman rule, when the blacksmiths developed increasingly their mastery from the military, which until then had been the most important compared to the civilian. Plinio il Vecchio (Pliny the Elder in Italian) makes us know that even in his time (I century AD), the iron cost more and was even more wanted than silver and in Rome the first guild of blacksmiths masters was already born.

After the barbarian invasions, there was a long wait until the new millennium and the cultural and economic renaissance of Europe to find the blacksmiths at work in “grandeur” style.

The moansteries and the “itinerant blacksmith”

The spreading centers of the art of wrought- iron became the convents, where real schools were born.

Alongside these fixed centers the figure of the “itinerant blacksmith” became widespread: masters in the art of iron-melting, moving from town to town and putting their knowledge and skills at the service of those who could grant them a generous compensation. The raw material, the molten iron, was produced in a few large centers, generally in the vicinity of the mines. A revolution marked the new vertical furnaces born in 1200 in Germany, which for the first time in history made available large amounts of raw material.

The wrought Iron in Florence

Florence is considered a real cradle of iron working. In 1200 there was already a flourishing business. At that time most of the smiths, or “blacksmiths” as they were called at that time produced hand tools and miscellaneous equipment for agriculture.

The blacksmiths and iron working guild was one of the oldest guilds in the city, where they joined the iron-working masters gathered to have a greater influence and representativeness. It belonged to the “Arte Medie” (“Medium Arts” in Italian) and only later this corporation was joined to the “major arts”, like wool, for example, under the name of “nuova arte maggiore” (“new major art” in Italian). In this period of particularly intense struggle for recognition for social and economic position within the town, the guild of blacksmiths was represented by 12 deans, and once the situation was stable, they became only 6. The guild of blacksmiths had, among other things; some distinctive elements compared the other guild of that time: the journeymen blacksmiths enjoyed particular privileged positions, a very good salary, and also took part in the decisions of the corporation.

he objects that were produced at that time were frames for the textile industry, keys, nails, hooks, latches, hinges, fire shovels, tripods, studs, lanterns, gimlet, buckles and clasps. The raw material for these processes was obtained from some forges. Towards the end of 1200, the Florentine blacksmiths, in order to protect themselves from the competition by some other blacksmiths from the countryside, were able to obtain a decree which prevented these competitive activities.

In the following centuries Florence and Tuscany were the focus of a great development of the art of iron. Iron works for “Palazzo Strozzi” were built in the late fifteenth century by a famous blacksmith, “Nicholas il Grosso” (“Nicholas the Large” in Italian), known as “Caparra”, whose name already showed his skills and his physical strength, a required feature for this type of work. Even in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the wrought iron follows fashion trends and tastes of the time, with an enrichment of the work made possible from refining techniques. Fundamental elements of this art become the leaves and foliage.

Protagonist of Liberty

Alessandro Mazzucotelli

Born in Lodi, in a family of iron traders originally from Imagna valley, soon he moved to Milan, where he found a job as an apprentice with his brother Carlo, in the blacksmith shop of Defendente Oriani near the street “Aldo Manuzio”, and a shop which he later took over. Equipped with exceptional skills and creativity, able to give to iron that lithe and “flowery” aspect which was the dominant characteristic of Liberty, he soon became a required collaborator for renowned architects such as Giuseppe Sommaruga, Gaetano Moretti, Ernesto Pirovano, Franco Oliva, Ulisse Stacchini and Silvio Gambini. Mazzucotelli distinguished himself at the first International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art in Turin in 1902, and the following year carried out a trip to several European countries together with cabinetmaker Eugenio Quarter; when he returned back he started an activity as a teacher at “Umanitaria”. Since 1922 directed the School of Applied Arts ISIA in Monza, where his student would “inherent” the chair of “Gino Manara wrought iron”; He was also the President of the Venice International Biennial of Applied Arts..

Among the exhibitions he later attended we can mention: ‘Exposition Universelle et Internationale of Brussels” (1910) and “the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes” in Paris (1925).

The wrought Iron in Modern Times

The art and the magic of wrought iron, now universally recognized and appreciated, in their long history through the centuries and millennia have had also periods of decline and obfuscation. One of these, the last in chronological order, dating back to the eighteenth century, when particularly the triumph of architecture and aesthetic cold and calculated taste, was in search of a copy as close as possible to the classical perfection of the great masters of the Greeks ‘antiquity removed the space for the capabilities of blacksmiths to be expressed.

Even technological progress seemed to call into question the continuation of this unique art form: iron castings become more and more wanted, and that removes the space for activity and expressive skills of blacksmiths. It ‘a new approach to cultural and literary aesthetics like that of Romanticism, that gives new force to the art of the blacksmith, going as far as to theorize that the revival of the art cannot travel separately from growth and the establishment of a qualitative craftsmanship, and the one who brought back to life and dignity the wrought iron was a French architect, Viollet-le-Duc, who resumes this activity in style in Boulanger.

The rise of “art nouveau” or “liberty style” with its references to the natural world consecrates definitely to the craftsmen the art of wrought iron in contemporary times, creating a new space for the blacksmiths and iron masters where to exercise their creativity, creating shapes of fruits, flowers, animals, fish, birds and other ornaments with which to enrich objects of everyday life, that the art of wrought iron brings back in great vogue.

Even the temporary emergence of a school of thought as rationalism, in recent decades, has been a breakthrough element of the creativity of these extraordinary artisans-artists.

the Italian Artisanship

In contemporary craftsmanship, iron working plays an important role. Every Italian region has its own specialties and characteristics. There is a switch from the production of objects for the fireplace and the typical weather vanes which are present in every roof of Friuli, to chandeliers, coat racks, umbrella stands, signs and balustrades of Piedmont. In central Italy with iron which is wrought on hot coals, they produce a bit ‘everywhere fireplace equipment, farm implements and household items. The most skilled craftsmen are dedicated to the finest productions: gates, headboards, lamps, tables and various furnishings. In Gubbio, finally, the craftsmen are specialized in the restoration of the ancient medieval weapons.

In Sicily, this activity has common origins with those of other Italian regions, but then it developed following an architectural route. The Sicilian artisans have dedicated themselves to the production of windows, balconies and gates of baroque palaces inspired by Arabian architecture. In addition to these more refined objects, their production goes from farm tools and household, to items of furniture and medieval weapons.

Constancia Bags – Elegance is not being noticed but being remembered

The evolution of ceramics processing in human history

The Ancient and Noble Art of Silk